Aryan Invasion

Theory: Revising History to Change the

Future

Siddhartha

Jaiswal

Stanford Universit

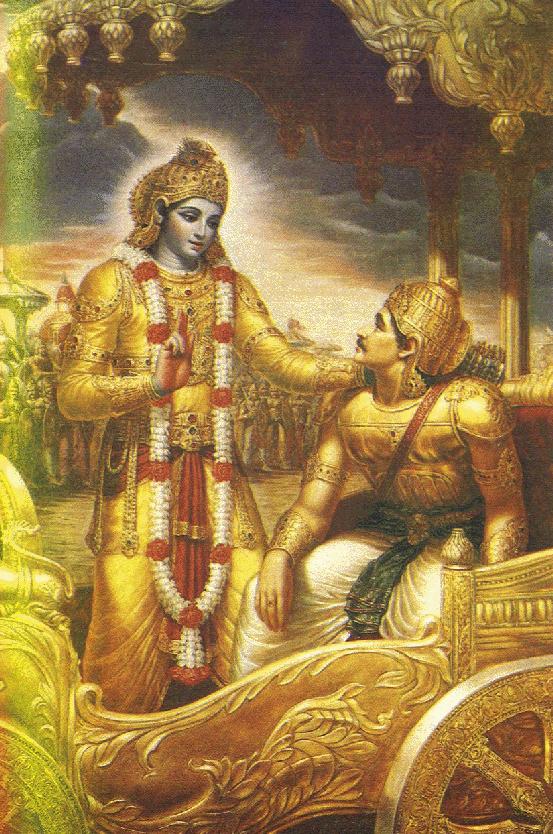

Growing up, I used to love

hearing my mother tell me the stories of the

Mahabharata

and the

Ramayana,

two of ancient India's greatest epic poems. Heroes

like Krishna, Rama, and Arjuna were my role models

and integral parts of my cultural identity. The

great war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas and

Rama's fourteen year trek through the jungles of

India and Lanka were not just fanciful children's

stories to me; this was Indian history, according

to our tradition. But once I entered grade school,

I was taught our history was wrong. Growing up, I used to love

hearing my mother tell me the stories of the

Mahabharata

and the

Ramayana,

two of ancient India's greatest epic poems. Heroes

like Krishna, Rama, and Arjuna were my role models

and integral parts of my cultural identity. The

great war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas and

Rama's fourteen year trek through the jungles of

India and Lanka were not just fanciful children's

stories to me; this was Indian history, according

to our tradition. But once I entered grade school,

I was taught our history was wrong.

According to the Western view of Indian history,

the Mahabharata was probably just a petty skirmish

between tribes, if it ever happened at all, and

Rama most likely never even existed. In fact, the

only thing definitive the textbooks said about

Indian history was that a group of tall,

fair-skinned nomads called Aryans invaded India,

displacing the native population and creating the

current Indian culture. All of Indian history, as

Indians understood it, was merely mythology or the

musings of some talented storyteller. Moreover, the

Indian civilization was not even indigenous to

India; rather, it was created by the same people

who had established civilization in Ancient Greece

and the Middle East.

What these textbooks said greatly undermined my

belief in my culture. It meant that all the stories

I heard as a child were just fantasy; it meant that

my culture was founded by violent barbarians; it

meant that everything my culture had accomplished

was lessened because it had a foreign origin.

Needless to say, I, as a thirteen year old boy, was

not flattered by this picture of my nation's past.

What I did not know then was that the Aryan

Invasion Theory (AIT), which has always been

disputed by prominent Indian scholars, was falling

into disrepute among current historians as well. I

learned much later that AIT was developed by

Eurocentric historians who had certain biases

regarding Indian culture. Today, however, AIT is no

longer accepted as fact. But why is the debate over

AIT such a pressing issue in modern India? The

answer is that AIT has several serious implications

for Indians, especially in our contemporary

society. First, a belief in a foreign origination

of Indian culture has marginalized the importance

of Indian history for many, like me. It has also

led many educated Hindus to develop feelings of

shame and a Eurocentric attitude toward their own

culture. Second, AIT has a decidedly negative

impact on the contemporary Indian political and

social fabric. It has created divisions between

North and South Indians, different ethnic groups,

and between castes. Finally, AIT needs to be

discarded by the very demands of historical truth.

The Indian psyche and social system has suffered

greatly because AIT, and some measure of justice

must be exacted before these wounds can heal. By

discrediting AIT, Indians can regain pride in their

ancient and glorious history, and use it as a

foundation to build a more united, stronger India.

In order to understand more fully the

damaging effects AIT has had in India, it is

necessary to examine the theory in some detail and

explore the biases and misconceptions of those who

originally proposed it. These late nineteenth

century scholars, who included such luminaries as

Max Muller and Max Weber, strongly believed in a

race of people known as Aryans who were the

ancestors and founders of culture in ancient

Greece, Mesopotamia, and India. The Aryans,

according to these scholars were tall,

fair-skinned, light-eyed nomads. The Aryans invaded

India around 1500 BC and displaced the

darker-skinned native population there, eventually

subjecting them to the Aryan culture and religion.

They forced the natives, known as Dravidians, to

move south and put them into the lowest castes of

Aryan society. Eventually, through centuries of

interbreeding and cultural miscegenation, the

current Hindu society was formed. The main evidence

for an Aryan race came from the fact that Sanskrit,

the classical language of ancient India, bore a

striking resemblance to Greek, Latin, and other

European tongues. This similarity gave rise to a

new language group: the Indo-European languages.

When, in the 1920s, the ancient cities of Harappa

and Mohenjodaro were discovered in northwest India,

they appeared to be abandoned for no apparent

reason. The invasion theorists took this as

evidence that an Aryan invasion had occurred, and

had displaced the earlier civilization. In order to understand more fully the

damaging effects AIT has had in India, it is

necessary to examine the theory in some detail and

explore the biases and misconceptions of those who

originally proposed it. These late nineteenth

century scholars, who included such luminaries as

Max Muller and Max Weber, strongly believed in a

race of people known as Aryans who were the

ancestors and founders of culture in ancient

Greece, Mesopotamia, and India. The Aryans,

according to these scholars were tall,

fair-skinned, light-eyed nomads. The Aryans invaded

India around 1500 BC and displaced the

darker-skinned native population there, eventually

subjecting them to the Aryan culture and religion.

They forced the natives, known as Dravidians, to

move south and put them into the lowest castes of

Aryan society. Eventually, through centuries of

interbreeding and cultural miscegenation, the

current Hindu society was formed. The main evidence

for an Aryan race came from the fact that Sanskrit,

the classical language of ancient India, bore a

striking resemblance to Greek, Latin, and other

European tongues. This similarity gave rise to a

new language group: the Indo-European languages.

When, in the 1920s, the ancient cities of Harappa

and Mohenjodaro were discovered in northwest India,

they appeared to be abandoned for no apparent

reason. The invasion theorists took this as

evidence that an Aryan invasion had occurred, and

had displaced the earlier civilization.

In formulating this theory, the proponents of

AIT had very set ideas about race and culture.

"European thinkers of the era were dominated by a

racial theory of man, which was interpreted

primarily in terms of color" (Frawley 1996). In

this era of European expansionism and colonialism,

Europeans had enslaved much of Africa, Asia, and

the Americas. The European conquerors were

primarily white, and the conquered peoples were

primarily dark-skinned. Similarly, the Aryan

Invasion was seen as a racial group with a common

culture and language who came to India and

dominated all those who were different racially or

spoke a different language. They assumed that the

original speakers of Indo-European language had to

be lighter skinned; thus, the darker-skinned Hindus

could not have been the original speakers. However,

scholars are only now realizing that the simplicity

of AIT does not explain the enormous complexity of

Indian culture and society, nor does it even fit

with the known facts. "The Aryan invasion theory is

an example of European colonialism turned into a

historical model" (Frawley 1994). AIT was certainly

not the work of objective and open-minded scholars.

In addition, those who proposed the

theory were often ardent nationalists or

Christians, opposed to anything that would glorify

a great culture of non-European, non-Christian

origin. Max Muller had set the date for Aryan

invasion at 1500 BC But Muller's basis for such a

date was completely speculative. "Max Muller, like

many of the Christian scholars of his era, believed

in Biblical chronology" (Frawley 1994). Given then

that the world was created in 4000 BC and the flood

occurred in 2500 BC, it was impossible to give the

Aryan invasion a date earlier than 1500 BC Also,

many of these scholars had dubious credentials and

motives. "Max Muller in fact had been paid by the

East Indian Company to further its colonial aims,

and others like Lassen and Weber were ardent German

nationalists, with hardly any authority on India,

only motivated by the superiority of German

race/nationalism through white Aryan race theory"

(Agarwal 1995). In addition, those who proposed the

theory were often ardent nationalists or

Christians, opposed to anything that would glorify

a great culture of non-European, non-Christian

origin. Max Muller had set the date for Aryan

invasion at 1500 BC But Muller's basis for such a

date was completely speculative. "Max Muller, like

many of the Christian scholars of his era, believed

in Biblical chronology" (Frawley 1994). Given then

that the world was created in 4000 BC and the flood

occurred in 2500 BC, it was impossible to give the

Aryan invasion a date earlier than 1500 BC Also,

many of these scholars had dubious credentials and

motives. "Max Muller in fact had been paid by the

East Indian Company to further its colonial aims,

and others like Lassen and Weber were ardent German

nationalists, with hardly any authority on India,

only motivated by the superiority of German

race/nationalism through white Aryan race theory"

(Agarwal 1995).

To what ends was AIT used by the colonizers in

India? It served primarily as a tool for

justification of the British presence in India. The

British argued that they were doing only what had

been done by the Aryans centuries before (Agarwal

1995). In effect, it gave the British a way to

rationalize their brutal exploitation and

domination of India. It also seemed to lessen the

severity of the equally brutal Muslim invasions of

India prior to the British arrival. This is perhaps

the most terrible use of AIT by the historians.

India was described as a land dominated by

foreigners ever since its inception. Karl Marx even

wrote that the whole history of India was a series

of invasions (Sukhwal 1971). How could such a

"dominated" people find value and pride in their

culture? Of what use were Rama and Krishna when

they inevitably lost to the hordes of barbarians

that plundered India?

The British also used AIT to 'divide and

conquer' India. "They promoted religious, ethnic,

and cultural divisions among their colonies to keep

them under control" (Frawley 1996). Often, various

principalities and kingdoms were played off against

each other by inciting regional or cultural

tensions in order to make British domination that

much easier. Unfortunately, many of these divisions

are still present in Indian society today.

The primary schism caused by AIT is

the north/south divide of India along racial lines.

The European scholars interpreted certain verses in

the Vedas (Hinduism's oldest surviving texts),

which described wars between lightness and

darkness, to mean that clashes between

light-skinned Aryans and dark-skinned Dravidians

occurred (Frawley 1996). As evidence for their

claim, they point to the constant references to

people described as 'Aryan' in the Vedas. However,

this is a skewed interpretation of Hindu texts

based on European ideals. "In Vedic literature, the

word Arya is nowhere defined in connection with

either race or language" (Agarwal 1995). Arya,

instead, is a title of respect, similar to the

English title 'sir'. An Aryan is one who is truly

noble by his deeds, intelligence, and sense of

duty: "Intrinsically, in its most fundamental

sense, Arya means an effort or an uprising and

overcoming" (Aravind 1996). In the Vedas, many of

the defeated kings of supposedly Dravidian stock

are described as Aryan. Many of these kings also

trace back their lineage to Manu, the first man, as

do the 'Aryan' kings. There simply is no Vedic

evidence of a racial connotation for the term Arya.

Eventually, a number of the European scholars,

including Max Muller, recanted their belief that

Aryan denoted a race. However, this was largely

ignored by others who became enamored by the idea

of an Aryan race and exploited this idea for

political gain. The primary schism caused by AIT is

the north/south divide of India along racial lines.

The European scholars interpreted certain verses in

the Vedas (Hinduism's oldest surviving texts),

which described wars between lightness and

darkness, to mean that clashes between

light-skinned Aryans and dark-skinned Dravidians

occurred (Frawley 1996). As evidence for their

claim, they point to the constant references to

people described as 'Aryan' in the Vedas. However,

this is a skewed interpretation of Hindu texts

based on European ideals. "In Vedic literature, the

word Arya is nowhere defined in connection with

either race or language" (Agarwal 1995). Arya,

instead, is a title of respect, similar to the

English title 'sir'. An Aryan is one who is truly

noble by his deeds, intelligence, and sense of

duty: "Intrinsically, in its most fundamental

sense, Arya means an effort or an uprising and

overcoming" (Aravind 1996). In the Vedas, many of

the defeated kings of supposedly Dravidian stock

are described as Aryan. Many of these kings also

trace back their lineage to Manu, the first man, as

do the 'Aryan' kings. There simply is no Vedic

evidence of a racial connotation for the term Arya.

Eventually, a number of the European scholars,

including Max Muller, recanted their belief that

Aryan denoted a race. However, this was largely

ignored by others who became enamored by the idea

of an Aryan race and exploited this idea for

political gain.

In fact, this idea of North and South Indians

being explicitly different has been a major source

of tension in the modern Indian republic. According

to Romila Thapar, a professor of Ancient Indian

history, "The theory of Aryan race has not only

served cultural nationalism in India but continues

to serve Hindu revivalism and, inversely,

anti-Brahman movements" (Thapar 1992). After India

gained independence in 1949, there was a call for

reorganization of Indian states on the basis of

language and cultural identity. A Dravidian

movement in South India, encouraged by the idea of

Aryan domination of Dravidian people, developed in

several southern states. Its goal was nothing short

of secession, and creation of a 'Dravinadu' nation.

Fortunately, the movement never gained force, but

it left wide rifts between North and South India.

In its wake came the formation of the Dravida

Munnetra Kazhagam party in 1967. Their basic

platform was that "Dravidians, the folk of South

India, were systematically expropriated and

enslaved by Brahmans and their ideology of

brahmanical superiority, which they-originally

migrants from North India-derived from the Sanskrit

texts of north-Indian Hindu injunctive culture"

(Stern 1993). These Dravidian movements have lasted

to the present and continue to have an affect in

Indian politics and serve to divide the nation.

There is, however, no logical basis for

this schism. Other than linguistic differences,

North and South India share much of the same

culture and religion. The major cause of this undue

tension is the belief in separate Aryan and

Dravidian races. Some historians have classified

the Indian pantheon of deities into two types:

Northern gods and Southern gods. Vishnu is

supposedly the most prominent Northern god because

he is mentioned several times in the Vedas. Shiva

is not considered an Aryan god because he is not

prominent in the Vedas. However, Shaivism and

hero-worship of Krishna are common throughout

India. My family, which is North Indian, worships

both of these figures. I have never been taught

that darker-skinned gods are Dravidian and

therefore inferior. In fact, Rama and Krishna are

both depicted as dark complexioned, and they are

the most famous of all the Indian heroes.

Unfortunately, though there is no true division of

Hinduism into Northern and Southern sects, regional

differences in culture have been exploited and used

to divide India. There is, however, no logical basis for

this schism. Other than linguistic differences,

North and South India share much of the same

culture and religion. The major cause of this undue

tension is the belief in separate Aryan and

Dravidian races. Some historians have classified

the Indian pantheon of deities into two types:

Northern gods and Southern gods. Vishnu is

supposedly the most prominent Northern god because

he is mentioned several times in the Vedas. Shiva

is not considered an Aryan god because he is not

prominent in the Vedas. However, Shaivism and

hero-worship of Krishna are common throughout

India. My family, which is North Indian, worships

both of these figures. I have never been taught

that darker-skinned gods are Dravidian and

therefore inferior. In fact, Rama and Krishna are

both depicted as dark complexioned, and they are

the most famous of all the Indian heroes.

Unfortunately, though there is no true division of

Hinduism into Northern and Southern sects, regional

differences in culture have been exploited and used

to divide India.

This problem of the north/south divide

is indicative of an even larger problem in India:

the question of national unity. If one accepts that

modern India is the result of an Aryan invasion of

a random assortment of native tribes and peoples,

then the question of Indian unity is resoundingly

negative. This, in fact, is the view that many

British scholars had of India. Sir John Seeley, a

British historian, wrote in 1883: This problem of the north/south divide

is indicative of an even larger problem in India:

the question of national unity. If one accepts that

modern India is the result of an Aryan invasion of

a random assortment of native tribes and peoples,

then the question of Indian unity is resoundingly

negative. This, in fact, is the view that many

British scholars had of India. Sir John Seeley, a

British historian, wrote in 1883:

The notion that India is a

nationality rests upon that vulgar error which

political science principally aims at eradicating.

India is not a political name, but only a

geographical expression, like Europe or Africa. It

does not mark the territory of a nation and a

language, but the territory of many nations and

many languages (Handa 1983).

The result of this type of thinking has lasted

into the present, and has led to calls for

secession from all sorts of ethnic groups ranging

from Punjabis to Bengalis to Keralis. Fortunately,

there have been voices which have opposed this

colonial mindset and brought to light the cultural

unity of India. Sardar K.M. Panikkar, a

Congressman, stated that "there was no such thing

as Assamese, Bengali or Kerala culture; there was

only one Indian culture which emanated from the

Mahabharata and the Ramayana"

(Sukhwal 1971).

In fact, all of the Vedic rishis are

in agreement that, according to scripture, there

was only one Indian culture, and it was founded by

Manu at the time of the flood. Swami Vivekananda, a

Hindu guru who toured the West in the late

nineteenth century, wrote: "The only explanation

can be found in the Mahabharata, which says that in

the beginning of Satya Yuga there was only one

caste, the Brahmanas, and then by difference of

occupation they went on dividing themselves into

castes" (Vivekananda 1893). Madhav M. Deshpande, of

the Department of Linguistics at the University of

Michigan, asserts that, "If we remove the mantle of

mythology and mysticism, the classical Indian

literature shows an awareness of this notion of

India as a cultural area" (Deshpande 1983). Thus,

according to Indian history, India was in the past

a unified nation of one people with a common

tradition and culture. Only by accepting a European

view of Indian history does the notion of a divided

India arise. Unfortunately, those who receive a

Westernized education, like me, only see the

European view of world history. In fact, all of the Vedic rishis are

in agreement that, according to scripture, there

was only one Indian culture, and it was founded by

Manu at the time of the flood. Swami Vivekananda, a

Hindu guru who toured the West in the late

nineteenth century, wrote: "The only explanation

can be found in the Mahabharata, which says that in

the beginning of Satya Yuga there was only one

caste, the Brahmanas, and then by difference of

occupation they went on dividing themselves into

castes" (Vivekananda 1893). Madhav M. Deshpande, of

the Department of Linguistics at the University of

Michigan, asserts that, "If we remove the mantle of

mythology and mysticism, the classical Indian

literature shows an awareness of this notion of

India as a cultural area" (Deshpande 1983). Thus,

according to Indian history, India was in the past

a unified nation of one people with a common

tradition and culture. Only by accepting a European

view of Indian history does the notion of a divided

India arise. Unfortunately, those who receive a

Westernized education, like me, only see the

European view of world history.

Not only has AIT served to justify British

conquest of India and divide the country on racial

and ethnic lines, but it has also had a negative

effect on Indian nationalism. Perhaps the single

greatest blow to Indian nationalism dealt by AIT

was its denial and marginalization of Indian

history according to Indians. Indian history is

seen as secondary to the history of the West. The

Vedic culture is considered to be an offshoot of

Middle Eastern cultures. The sciences of India were

also considered to be derived from the Greeks.

Vedic advances in astronomy and mathematics were

largely ignored because of the 'primitive' nature

of the Vedic culture. AIT also discredited many of

the great historical works of Indian literature,

such as the Mahabharata, Ramayana,

and the Puranas. All of the great Indian

heroes, including my favorites Rama and Krishna,

were dismissed as fictional characters without

historical basis. This rejection of Indian

tradition is tantamount to "disowning and

discarding the very basis and raison d'être

of the Hindu civilization" (Agarwal 1995). The net

result of this demeaning of Indian culture was to

generate feeling of shame at Hindu culture, a

feeling that "its basis is neither historical nor

scientific, but only imaginary, while being

actually rooted in invasion and oppression"

(Frawley 56). It made Hindus feel like their

culture was based on the writings of nomadic

barbarians and was inherently inferior to the

Western civilization.

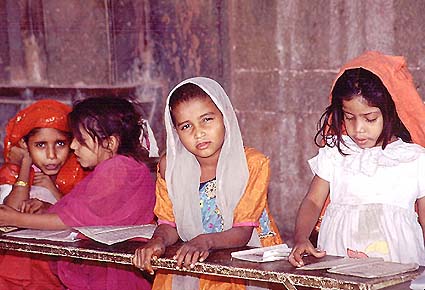

Even in India today, schools teach

Western views of Indian history and use European

translations of the great texts. Children are being

taught that their culture is inherently inferior to

the Western tradition and that Hinduism is an

archaic and outdated pagan religion. This creates a

dichotomy within the educated Indian's mind between

observing tradition and risk being considered

'backward', or rejecting Indian culture altogether

in favor of a more rational, Western attitude. It

is not surprising that the notion of an Aryan

invasion was welcomed by some Indians who accepted

the Western view of Indian civilization: "There was

an appeal to some middle class Indians that the

coming of the English represented a reunion of

parted cousins, the descendants of two different

families of the ancient Aryan race" (Thapar 1992).

For the Indian living in a Western society, this

dichotomy is at the forefront of his identity. For

me, accepting Indian culture and tradition after

reading about it in Western books was a difficult,

if not impossible task. Not until I discovered the

dubious origins and factual inconsistencies of AIT,

and the implications therein, did I could regain

the sense of pride I once found by reading the

stories of Rama and Krishna. Even in India today, schools teach

Western views of Indian history and use European

translations of the great texts. Children are being

taught that their culture is inherently inferior to

the Western tradition and that Hinduism is an

archaic and outdated pagan religion. This creates a

dichotomy within the educated Indian's mind between

observing tradition and risk being considered

'backward', or rejecting Indian culture altogether

in favor of a more rational, Western attitude. It

is not surprising that the notion of an Aryan

invasion was welcomed by some Indians who accepted

the Western view of Indian civilization: "There was

an appeal to some middle class Indians that the

coming of the English represented a reunion of

parted cousins, the descendants of two different

families of the ancient Aryan race" (Thapar 1992).

For the Indian living in a Western society, this

dichotomy is at the forefront of his identity. For

me, accepting Indian culture and tradition after

reading about it in Western books was a difficult,

if not impossible task. Not until I discovered the

dubious origins and factual inconsistencies of AIT,

and the implications therein, did I could regain

the sense of pride I once found by reading the

stories of Rama and Krishna.

Over the past fifteen years, a

tremendous amount of new evidence has surfaced that

refutes the Aryan Invasion Theory. Provided here is

a brief summary of some of the evidence to date.

First, there is absolutely no evidence of a foreign

origin for the so-called Aryans in any of the

Indian texts. The Vedas, the most important and

oldest texts in the Hindu religion, make no mention

of foreign lands or invasions (Talageri 1993). If

the Vedas are the foundational texts of the Aryans,

why do they not make mention of anything outside of

India? Over the past fifteen years, a

tremendous amount of new evidence has surfaced that

refutes the Aryan Invasion Theory. Provided here is

a brief summary of some of the evidence to date.

First, there is absolutely no evidence of a foreign

origin for the so-called Aryans in any of the

Indian texts. The Vedas, the most important and

oldest texts in the Hindu religion, make no mention

of foreign lands or invasions (Talageri 1993). If

the Vedas are the foundational texts of the Aryans,

why do they not make mention of anything outside of

India?

Second, new archaeological findings at the

ancient sites of the Harappan culture show no

evidence of a foreign invasion. These sites, which

supposedly predate Vedic culture by at least a

thousand years, show evidence of Vedic religious

practice (Agarwal 1995). In addition, the lost city

of Dwaraka, which is mentioned in the Mahabharata

as being gradually submerged into the ocean, was

recently found in the Arabian Sea off the coast of

Gujarat, and dated at 3000-1500 BC This confirms

both the antiquity of the Mahabharata and

Ramayana, as well as the historical truth of

the works. Also, a study of ancient Middle Eastern

cultures has shown evidence of a thriving Vedic

culture for a thousand years after the

Harappan culture, suggesting an east to west

migration of people from India, and not vice

versa.

Third, new philological evidence has

surfaced with the deciphering of the Harappan

civilization script. The script has been deciphered

by Dr. S.R. Rao, and has been confirmed to be of an

Indo-Aryan base. Hence, the inhabitants of the

Harappan civilization could not have been

Dravidians, as proposed in AIT. Third, new philological evidence has

surfaced with the deciphering of the Harappan

civilization script. The script has been deciphered

by Dr. S.R. Rao, and has been confirmed to be of an

Indo-Aryan base. Hence, the inhabitants of the

Harappan civilization could not have been

Dravidians, as proposed in AIT.

Finally, there is no racial evidence that there

is any real racial difference among the peoples of

India. In fact, according to a recent landmark

study of race (The History and Geography of Human

Genes), Europeans, Middle Easterners, and all

Indians belong to a single race of Caucasian type

(Agarwal 1995). In addition, anthropological

evidence indicates that the inhabitants of ancient

Gujarat and Punjab are ethnically the same as the

present day populations of those areas (Frawley

1994).

The reevaluation of history occurring in India

is part of a larger, growing trend of non-European

cultures to rectify the injustices done to their

nations' histories. The implications for India, and

for the world at large, are significant. For India,

the refutation of AIT places Hinduism and the

culture of India in a much older and significant

context in the annals of history. If AIT is

rejected, it would mean that the Vedas are the

oldest religious texts in the world, Hinduism the

oldest surviving religion, and the Indian culture

the oldest living culture in the world. It would

also serve to unify the country by proving its past

solidarity and the common history of its peoples.

Finally, it would put Indian literature and

science, long regarded as primitive, into a place

of historical importance. But the larger

implications of challenging AIT are as equally

important. If Indian scholars can successfully

challenge what has long been regarded as truth by

the European tradition, then other cultures will

also have the same hope of rewriting their

histories from a non-Western point of view. For too

long, the development of Western civilization has

been regarded as the only important one in world

history, with other equally important cultures

given only token acknowledgment. After all, how a

culture views itself historically ultimately

determines what kind of future it can build. And

finally, the refuting of AIT will help heal wounds

on a personal level. I know that discovering that

AIT is not necessarily factually true has made me

come to terms with my culture and helped me learn

to respect the greatness of its tradition. My hope

is that it will help others to do the same.

References

References

Aravind, Yogi. (1996). Arya: Its

Significance [Online]. Aryan Invasion Theory

Links. Available Internet:

http://rbhattnagar.ececs.uc.edu:8080/hindu_history/ancient/aryan/

aryan_link.html

Agarwal, Dinesh. (1995, November 8). Demise of

Aryan Invasion/Racial Theory [Online]. Available

Internet: NEWS:

soc.religion.hindu

Deshpande, Madhav M. (1983). Nation and Region:

A Socio-Linguistic perspective on Maharashtra. In

Milton Israel (Ed.), National Unity: The South

Asian Experience (pp. 111-134). New Delhi:

Promilla.

Frawley, David. (1996). The Aryan-Dravidian

Controversy [Online]. Aryan Invasion Theory

Links. Available Internet:

http://rbhattnagar.ececs.uc.edu:

8080/ hindu_history/ancient/aryan/

aryan_link.html

Frawley, David. (1994). The Myth of the Aryan

Invasion of India. New Delhi: Voice of

India.

Handa, Madan L. (1983). National Unity, Social

Justice and Education: The Indian Experience. In

Milton Israel (Ed.), National Unity: The South

Asian Experience (pp. 47-76). New Delhi:

Promilla.

Stern, Robert W. (1993). Changing India.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sukhwal, B.L. (1971). India: A Political

Geography. New Delhi: Allied.

Talageri, Shrikant G. (1993). The Aryan

Invasion Theory: A Reappraisal. New Delhi:

Aditya Prakashan.

Thapar, Romila. (1992). Interpreting Early

India. New Delhi. Oxford Universiy Press.

Vivekananda, Swami. (1893). [Speech in Madras].

Aryan Invasion Theory Links. Available

Internet:

http://rbhattnagar.ececs.uc.edu:

8080/ hindu_history/ancient/aryan/

aryan_link.html

|